Question:

Dear Rabbi Singer,

I am a Lutheran living in Switzerland and have been reading your web page with interest. I admire your commitment to your faith, yet I am perplexed as to why you so assuredly reject Jesus Christ as your messiah. He came not only for the gentiles, but for the Jews as well. He was born to a Jewish mother and came to the Jewish people.

Because you are a rabbi, I am particularly perplexed as to why you have not willingly accepted Christ. You surely have read the 22nd Psalm which most clearly speaks of our Lord’s crucifixion. Read verse 16. It states, “Dogs have compassed me; the assembly of the wicked has enclosed me; they pierced my hands and my feet.” Of whom does the prophet speak other than our Lord? This Old Testament prophecy could only be foretelling Jesus’ unique death on the cross. What greater proof is needed that Jesus died for the sins of mankind than this chapter which was written a thousand years before Jesus walked this earth?

I know that the Jews have been maligned and persecuted by so-called Christians. This has certainly left a bad taste in the mouths of the Jewish people against Christ; but certainly you must know, rabbi, that these were not real Christians, for a believer in Christ must love the Jew, for his Savior is a Jew. Many Jewish people accuse Christians of anti-Semitism, and one can understand from where this bias is coming; for the Jews have been persecuted by those who claim to be Christian, but they are not. The true Christian loves the Jewish people.

Yours,

Answer:

This is certainly one of the more surprising letters that I have received in recent memory. There is nothing about your question that is unusual or uncommon; I receive questions about this most-debated Psalm regularly. It is rather the denomination with which you proudly identify that caught me by surprise.

How odd that a Lutheran would proclaim that the tormentors of the Jews “were not real Christians,” yet you apparently are not embarrassed to identify yourself with a denomination that is named after and founded on the teachings of Martin Luther. Among all the Church Fathers and Reformers, there was no mouth more vile, no tongue that uttered more vulgar curses against the Children of Israel than this founder of the Reformation whom you apparently revere. Even the anti-Semitism of the New Testament and the church fathers pales in comparison to the invectives launched by Luther’s impious tongue during his lifetime.

In your letter you declared with certainty that those “so-called Christians” who “maligned and persecuted” the Jewish people “were not real Christians.” Do you believe that the founder of your church, Martin Luther, should be counted among those who are not real Christians? Have you not read his odious volume entitled, Of the Jews and Their Lies? If you are familiar with this and other indecent works of Luther, do you also believe that this German Reformer lost his salvation because his maniacal hatred for the Jew prevented him from being an upstanding member of Christendom? If this is in fact what you believe, why would you belong to a church that boasts his unblessed name?

[box style=”solid”]

For Luther’s complete work “Of the Jews and Their Lies,” Click Here

[/box]

The consistent and unyielding pattern of Jew-hatred that has for so long gripped the imagination of the true believer cannot be attributed to coincidence or to a remarkable quirk of history.

The accounts in the New Testament—the most cherished book of the devout Christian—already display the animus of the early Church toward the Jews, portraying them as the people of the devil: cunning, traitorous, corrupt, deceitful, and conspiring. In essence, whatever it is that humanity abhors, that is precisely how the Jews are depicted in the Christian Bible. Without rest, post-canonical Christian literature continued to perpetuate this dark image of the Jew. There can be little doubt as to why Christians believe of the Jews what common sense would forbid them to believe of anyone else. To some extent, Luther and his countless followers who eagerly embraced his shameful message were together willing followers of a body of literature that scandalized, smeared, and ultimately condemned the children of Israel to an unimaginable history.

Moreover, in an effort to distance Christians from a compelling Jewish message, the founders and defenders of Christianity methodically altered selected texts from the Jewish scriptures. This rewriting of Tanach was not done arbitrarily or subtly. The Church quite deliberately tampered with the words of the Jewish Scriptures in order to bolster their most startling claim: The Old Testament clearly foretold that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah. With this goal in mind, missionaries manipulated, mis- quoted, mistranslated, and even fabricated verses in Tanach in order to make Jesus’ life fit traditional Jewish messianic parameters and to make traditional Jewish mes- sianic parameters fit the life of Jesus.

Bear in mind, the Jewish Scriptures were written in Hebrew, not in seventeenth century King James English. What has made Christian believers so vulnerable to Bible tampering is that almost none of them can read or understand the Hebrew Bible in its original language. Virtually no Christian child in the world is taught the Hebrew language as part of a formal Christian education. As you and countless other Christians earnestly study the Authorized Version of the Bible, there is a blinding yet prevailing assumption that what you are reading is Heaven-breathed. Tragically, virtually every Christian in the world reads the translation of men rather than the Word of God. On the other hand, every Jewish child in the world who is enrolled in a Jewish school is taught to read and write Hebrew long before he or she even heard the name of Luther.

Unbeknownst to you and parishioners worldwide, the King James Version and numerous other Christian Bible translations were meticulously shaped and painstakingly retrofitted in order to produce a message that would sustain and advance Church theology and exegesis. This aggressive rewriting of biblical texts has had a devas- tating impact on Christians throughout the world who unhesitatingly embrace these corrupt translations. As a result, Christians earnestly wonder, just as you have, why the Jews, who are the bearers and protectors of the divine oracles of God, have not willingly accepted Jesus as their messiah.

What evangelicals fail to understand, however, is that the passionate resistance of the Jew to the teachings of Christianity has little to do with the Church’s bad manners. Rather, it is the direct result of the Church’s contrived and therefore implausible message. This stunning conclusion, however, is impossible for Christians to accept without bringing injury to their own faith and worldview.

In Christian theology the Jews are not portrayed as a tribe whose beliefs conflict with the teachings of the Church. Quite the contrary, the religion of Christianity readily concedes that the Jews were God’s “firstborn”—the people who were chosen to receive and protect the divine Oracles of God. The spiritual principles of such a priestly nation cannot be dismissed lightly. As a result, Christendom systematically engaged in a thorough ad hominem assault against the Jewish people, slandering them as a nefarious, demonic nation. It isn’t difficult to understand how polemical literature against the Jews became a common feature in Church writings. By declar- ing that the Jew rejects the claims of the Church as a result of Christian anti- Semitism, as you insist, or the Jew’s spiritual blindness, evangelicals spare them- selves the festering anguish that self-searching and self-doubt invariably create.

To understand the brazen manner in which Christendom tampered with the Jewish scriptures, let’s examine the verse that you insist “proves” that Jesus is the messiah. Psalm 22:16 in the King James Version (KJV) reads,

Dogs have compassed me; the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me; they pierced my hands and my feet.

Understandably, Christians are confident that this passage contains a clear reference to Jesus’ crucifixion. “Of whom other than Jesus could the Psalmist be speaking?” missionaries ask. They insist that the Bible could not be referring to any other person in history but the savior who bore the marks of the Cross.

[one_half valign=”top” animation=”none”]

Apparently, you were so impressed by this argument that you wondered how a rabbi like myself could miss this reference to Jesus’ crucifixion. Paradoxically, well-educated Jews are utterly repelled by the manner in which the church rendered the words of Psalm 22:17. ((Although in a Jewish Bible this verse appears as Psalm 22:17, in a Christian Bible it appears as 22:16. So as not to create confusion, I refer to this controversial verse as Psalm 22:17 throughout this article.))

[/one_half]

[one_half_last valign=”top” animation=”none”]

[box style=”solid”]

Whereas in a Jewish Bible this verse appears as Psalm 22:17, in a Christian Bible it appears as 22:16. To avoid confusion, this verse will be referred to as Psalm 22:17 throughout this article.

[/box]

[/one_half_last]

Psalm 22:17 (16) |

||

Correct Translation |

Hebrew |

King James Version (16) |

|

For dogs have encompassed me; a company of evildoers have enclosed me; like a lion, they are at my hands and my feet. |

כִּי סְבָבוּנִי, כְּלָבִים: עֲדַת מְרֵעִים, הִקִּיפוּנִי; כָּאֲרִי, יָדַי וְרַגְלָי: |

For dogs have compassed me, the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me; they pierced my hands and my feet. |

Notice that the English translation from the original Hebrew does not contain the word “pierced.” The King James version deliberately mistranslated the Hebrew word kaari (כָּאֲרִי) as “pierced,” rather than “like a lion,” thereby drawing the reader to a false conclusion that this Psalm is describing the Crucifixion. The Hebrew word כָּאֲרִי does not mean pierced but plainly means “like a lion. The end of Psalm 22:17, therefore, properly reads “like a lion they are at my hands and my feet.” Had King David wished to write the word “pierced,” he would never have used the Hebrew word kaari. Instead, he would have written either daqar or ratza, which are common Hebrew words in the Jewish Scriptures. These common words mean to “stab” or “pierce.” Needless to say, the phrase “they pierced my hands and my feet” is a not-too-ingenious Christian contrivance that appears nowhere in Tanach.

Bear in mind, this stunning mistranslation in the 22nd Psalm was not born out of ignorance. Christian translators were well aware of the correct meaning of this simple Hebrew word. They fully understood the meaning of the word כָּאֲרִי and deliber- ately twisted their translations of this text. The word kaari can be found in many other places in the Jewish scriptures and they correctly translated כָּאֲרִי “like a lion” in all places in Christian Bibles where this word appears with the exception of Psalm 22—the Church’s cherished “Crucifixion Psalm.”

For example, the identical word kaari is also found in Isaiah 38:13. In the immediate context of this verse King Hezekiah is singing a song for deliverance from his grave illness.In the midst of his supplication he exclaims in Hebrew “שִׁוִּ֤יתִי עַד־בֹּ֙קֶר֙ כָּֽאֲרִ֔י” Notice that the last word in this phrase (moving from right to left) is the same Hebrew word kaari that appears in Psalm 22:17. In this Isaiah text, however, the King James Version correctly translates these words “I reckoned till morning that, as a lion…” As mentioned above, Psalm 22:17 is the only place in all of the Jewish Scriptures that any Christian Bible translates kaari as “pierced.”

It must be noted that the authors of the New Testament were not responsible for inserting the word “pierced” into the text of Psalm 22:17. This verse was tampered with long after the Christian canon was completed. Bear in mind, during the latter half of the first century, when the New Testament writers were compiling their Greek manuscripts, Psalm 22:17 was still in pristine condition; thus, when the authors of the New Testament read this verse, they found nothing in the phrase “ like a lion they are at my hands and my feet” that would advance their teachings. As a result, Psalm 22:17 is never quoted in the New Testament. Missionaries, who insist that the Christian translation of this verse reflects the original words of King David, must wonder why there was not one New Testament author who deemed this supposed allusion to the crucifixion worthy of being mentioned in his writings.

A cursory reading of the entire 22nd Psalm reveals the extent to which this verse was subjected to reckless tampering. Throughout this chapter, King David routinely uses an animal motif to describe his enemies. The Psalmist’s poignant references to the “dog” and “lion” are, therefore, common metaphors employed by the Psalmist. In fact, David repeatedly makes reference to the “dog” and “lion” both before and after Psalm 22:17. For King David, these menacing beasts symbolize his bitter foes who continuously sought to destroy him. This metaphor, therefore, sets the stage for the moving theme of this chapter. Although David’s predicament at times seems hope- less, this faithful king relied on God alone for his deliverance. As the Psalmist eagerly looks to God for deliverance from his adversaries, he conveys the timeless mes- sage that it is the Almighty alone Who can save the faithful in times of tribulation. Let’s examine a number of verses in this chapter that immediately surround Psalm 22:17 as they appear in the King James Version.

King David, the author of Psalm 22, identifies his enemies as “lions” in the verses that immediately precede and follow Psalm 22:17 (16). |

|

Psalm 22:12-13 (KJV) |

Psalm 22:20:21 (KJV) |

|

Many bulls have compassed me: strong bulls of Bashan have beset me round. (13) They gaped upon me with their mouths, as a ravening and a roaring lion. |

Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog. (21) Save me from the lion’s mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns. |

As mentioned above, it is obvious when reading this larger section of the 22nd Psalm that King David is using an animal motif—most commonly lions—as an animated literary device, in order to describe his pursuers and tormentors. This striking style is pervasive in this section of the Bible. In fact, each and every time the word “lion” appears in the Book of Psalms, King David is referring to a metaphoric lion, rather than a literal animal.

For example, in the 17th Psalm King David appeals to the Almighty to rescue him from the hands of his enemies, the “lion.” Bear in mind, an examination of the 17th Psalm is of great relevance to our study because in many respects Psalm 17 and 22 are sister chapters, both with regard to their literary motif and driving theme.

In the 17th Psalm, he is seeking deliverance from his adversaries as in Psalm 22. In Psalm 17:8-12, he pleads with God for deliverance from the “lion,” as he cries out,

Hide me under the shadow of Your wings, from the wicked who oppress me, from my deadly enemies, who compass me about. They are enclosed in their own fat; with their mouths they speak proudly. They have now compassed us in our steps; they have set their eyes bowing down to the earth, like a lion that is greedy of his prey, and as it were a young lion lurking in secret places.

Fearing that he has been abandoned by God, David implores the Almighty to answer his supplications for help, mitigating any question as to the identity of the Psalmist. It is explicitly clear from the very first verse of this chapter that the person speaking is King David.

“Lord, how long wilt thou look on? Rescue my soul from their destruction, my darling from the lions.”

Moreover, missionaries are confronted with another vexing problem in their effort to interpolate the words of this Psalm into a first century crucifixion story. In the simplest terms, this text that Christians eagerly quote is not a prophecy, nor does it speak of any future event. This entire Psalm, as well as Psalm 23:1-3 that follows, contains a famous personal prayer in which King David cried out to God from the depths of his pain and anguish—a fugitive from his family and former friends who betrayed him. Accordingly, the stirring monologue in this chapter is all in the first person. Fearing that he has been abandoned by God, David implores the Almighty to answer his supplications for help, mitigating any question as to the identity of the psalmist. It is explicitly clear from the very first verse of this chapter that the person speaking is King David.

Understandably, Trinitarian Christians are confronted with another staggering problem; attributing this to anyone other than David, i.e., Jesus, is nonsensical, considering that most Christians deem Jesus and God to be one entity. In the beginning of this chapter the Psalmist cries aloud,

“My God, my God, why have You forsaken me? Why are You so far from helping me, and from the words of my groaning? O my God, I cry in the daytime, but You do not hear; and in the night season, and am not silent.”

(Psalm 22:1-3)

Why would Jesus, whom Trinitarians insist is God, complain that “God is so far from helping me?” To whom was Jesus complaining? How could God, the first Person of the Trinity, not hear the cries of God—the second Person of the Trinity? To whom is this supposed god/man complaining? Finally, why would God be complaining to God? The Psalmist is confused and bewildered as he beseeches God, who he believes is silent. He feels as though his supplications were cast aside. In the verses that follow, David questions his feelings of abandonment when enumerating the times when God listened and intervened on behalf of his ancestors. If God and Jesus were truly one entity, then how or why would God not understand His own predicament? How can God wonder why God doesn’t hear His own prayers? Furthermore, who are God’s ancestors? Applying the words of Psalm 22 to Jesus challenges even the most fertile imagination and places an enormous strain on Church teachings.

The nagging question that comes to mind is: Why did the King James Version translate the Hebrew word כָּאֲרִי (kaari) in Isaiah 38:13 correctly, “like a lion,” yet deliberately mistranslate this same word as “pierced” in Psalm 22:17? Clearly, these Christian translators were well aware of the correct meaning of the word kaari, as evidenced by their translation of Isaiah 38:13. Why then did they specifically tamper with Psalm 22?

To fully understand why the Church felt compelled to revise the 22nd Psalm, it is essential to grasp the central role this famed chapter plays in traditional Christian teachings. The Church fathers cherished Psalm 22 as a chapter that explicitly des- cribes in vivid detail the agony of the Passion Narratives, and provides the Gospel’s script for Jesus’ crucifixion. Segments of this Psalm are quoted extensively in the New Testament as a fulfillment of an Old Testament prophecy of the crucifixion. The most notable quote from Psalm 22 appears in the first two Gospels and is found in the chapter’s opening verses, “My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?” Matthew and Mark place this “Cry of Dereliction” in the mouth of the crucified Jesus as his last dying words. ((In the book of Luke, Jesus’ last dying words are, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” In John’s Gospel, Jesus’ last words are “It is finished.”)) These two Gospels resourcefully use Psalm 22 as one of many palettes from which to paint the brutal picture of a tormented crucified savior. All of the Gospels ((Matthew 27:35; Mark 15:24; Luke 23:34; John 19:24.)) similarly use Psalm 22:19 (22:18 in a Christian Bible) in their crucifixion narratives, and Hebrews 2:12 quotes Psalm 22:23 to explain why the messiah had to suffer for humanity.

Psalm 22 has, therefore, always been a vital text to the Church and was used repeatedly in order to retroject the life of Jesus into the “Old Testament.” In so doing, missionaries sought to lend credibility to their claim that Jesus is the messiah as was foreordained by the ancient Jewish prophets. For Christendom, the Psalmist’s original intent was superseded by its interest in applying this entire chapter to Jesus’ passion, no matter how extensive the revisions would be. The Church, therefore, did not hesitate to tamper with the words of the 22nd Psalm so that its verses would reflect and sustain its Christian message. Isaiah 38:13, on the other hand, possessed no Christological value to the Church and was neither quoted nor used by the Church fathers to propagate their teachings. Christendom, therefore, had no need to mis-translate it, and Isaiah 38:13 was, accordingly, left intact.

Interestingly, the stunning mistranslation in this chapter did not escape the notice of the missionary world. In fact, this controversy has attracted quite a bit of attention from Christians dedicated to Jewish evangelism.

For example, Moshe Rosen, the founder of Jews for Jesus, advances a rather inventive response to this controversy over the appearance of the word “pierced” in Christian translations of Psalm 22. In his widely distributed book, Y’shua, Rosen readily concedes that the Hebrew word kaari does mean “like a lion,” and not “pierced”; yet it is on this very point where he makes his argument.

He suggests that although the word “pierced” does not exist in the Hebrew Masoretic text, it is possible that a scribe may have inadvertently changed the word “pierced” into “like a lion” by modifying one small Hebrew letter. In his own words he writes,

We can probably best understand what happened when we realize that, in Hebrew, the phrase “they have pierced” is kaaru while “like a lion” is kaari. The words are identical except that “pierced” ends with the Hebrew letter vav and “lion” with a yod. Vav and yod are similar in form, and a scribe might easily have changed the text by inscribing a yod and failing to attach a vertical descending line so that it would become a vav. ((Rosen, Moishe. Y’shua. Chicago: Moody, 1982, p. 45-46.))

While Rosen’s proposition is quoted frequently by missionaries, it contains numerous remarkable flaws. Transforming kaari (כָּאֲרִי) into kaaru (כָּאֲרוּ) by changing the letters kaf (כּ), alef (א), raish (ר), yod (י), which means “like a lion,” into kaf (כּ), alef (א), raish (ר), vav (ו) does not create the Hebrew word for “pierced,” as Rosen argues. In fact, kaaru doesn’t mean anything. In other words, this word kaaru does not exist in the Hebrew language; it’s little more than Semitic gibberish. Rosen’s claim that some anonymous scribe may have inadvertently changed kaaru into kaari is wholly unfounded and completely untenable.

In order to concoct a word that resembles kaaru, you would not only have to change the letter yod into a vav, but the letter alef would have to be removed altogether. This alteration would create the three-letter word karu (כָּרוּ),spelled kaf, raish, vav. Karu, however, does not mean “pierced” either. It means to “excavate” or “dig.”

As mentioned, the words used in Tanach for “pierce” or “stab” are daqar or ratza, never karu, which does not have the connotation of “piercing” – as in puncturing flesh.

For example, the King James Version renders אָזְנַיִם, כָּרִיתָ לִּי in Psalm 40:7 (verse 6 in a Christian Bible) metaphorically as “mine ears hast thou opened.” The Hebrew word כָּרִיתָ contains the same root as the word כארו (without the א aleph) that Christians claim is in Psalm 22:17, and it literally means “ears you have dug for me.”

The message contained in Psalm 40:7 is clearly conveyed by its context. By digging or excavating his ear, the Psalmist is able to hear and perceive what God did and didn’t desire. If karah could be translated as “pierce,” this would mean that the Psalmist is piercing or stabbing his ears to hear God more clearly! The word כרו means to “open” or “excavate,” not rip through flesh.

In recent years, a conservative, evangelical Christian professor of Religious Studies at Trinity Western University, Canada, argued that an ancient, second century manuscript supports the reading of “pierced” in Psalm 22. In his book, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible (2002), Dr. Peter Flint claimed that scraps of scroll found at the Nahal Hever Cave support the Christological reading rather than the Masoretic Text which clearly reads, “like a lion.” The Nahal Hever Cave is located about 30 km south of Qumran. The document Flint is making reference to is designated as 5/6HevPs.

Bear in mind that the Nahal Hever manuscripts are considerably younger than the Dead Sea Scrolls. While the Qumran Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts predate the first Jewish War (66 CE), the manuscripts from Nahal Hever came from a later period; between the two Jewish Wars (between 70 CE and 135 CE). Despite the claims made by Professor Flint in the Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, the passage in 5/6HevPs does not “unambiguously read pierced.”

Hebrew |

Translit. |

Meaning |

Comment |

|

כארי |

Kaari |

“Like a lion” |

This common word appears in all the Masoretic texts in the world. |

|

כארו |

Kaaru |

Does not exists in the Hebrew language |

Christians claim that this non- existent word means “pierced,” and appears in the Nahal Hever Cave. |

|

כרו |

Karu |

“Dig” or “excavate” |

The root of this word appears many times in Tanach. It does not mean to “pierce” through flesh. |

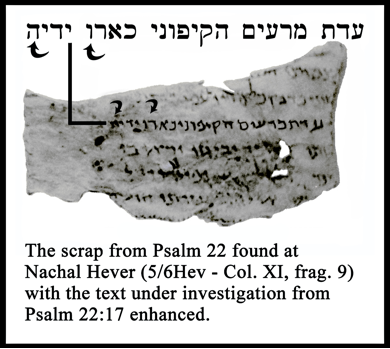

The above image was digitally enhanced, and it is difficult to discern by studying the faint, ancient text whether the word in question ends in a elongated י (yud) or a shortened ו (vav). Unlike other ancient texts, the writing on this script found at Nahal Hever is not sharp or uniform. If, for argument’s sake, we conclude that the debated word written in the Nahal Hever script is כארו (ka’aru), as Rosen and Flint argue, it is obvious that this anomaly is the result of the scribe’s poor handwriting or spelling mistake. There is clear evidence, in fact, from an obvious spelling mistake in the script itself that the second century scribe was not meticulous. The very next word after the debated word is “my hands.” The Hebrew word in Psalm 22:17 is ידי (yadai). The Nahal Hever scribe, however, misspelled this word [as well][/as] by placing an extra letter ה (hey) at the end of the word. Thus, the Nahal Hever 5/6HevPs reads ידיה instead of the correct ידי. The Hebrew word ידיה (yadehah) means “her hands,” not “my hands.”

Moreover, as explained above, there is no verb in the Hebrew language as כארו (ka’aru). In order to create the word “dig” or “excavate” in the Hebrew language, the א (aleph) would have to be removed from the word כארו as well. Again, כארו (ka’aru) is Hebrew gibberish.

Rosen is not the only church apologist to use scribes and rabbis of antiquity to defend the Christian translation of Psalm 22. In fact, missionaries more frequently refer to the Septuagint to justify the manner in which Christian Bible translators render Psalm 22:17. They argue that the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the entire Old Testament, which was completed by 72 rabbis more than 200 years before the Christian century, renders the last phrase of Psalm 22:17 as “they pierced my hands and my feet.” They conclude from this translation that even the rabbis who lived before the first century believed that the last clause of this verse reads “pierced” rather than “like a lion.”

Evangelists are typically quite fond of this response because it enables them to circumvent the often-troubling original Masoretic Hebrew Bible. This notion may seem strange at first glance. Yet, although Christians typically launch their assault on Judaism by swearing staunch allegiance to the Hebrew Scriptures, more often than not, they will renounce this vow in order to rescue their dubious proof-texts.

While somewhat secondary, the Church as well as Enlightenment philosophers such as Immanuel Kant have consistently held a more favorable view of Jews, i.e. the ancient Hebrews of the Old Testament who lived prior to the first century than those who lived during and after the death of Jesus. The Jewish translators of the Septuagint are of course pre-Christian, and are, therefore, held in higher regard in the eyes of the Christendom than those Jews who rejected the claims attributed to Jesus.

Despite the overwhelming popularity of the contention that the Greek translation of 72 rabbis supports the use of the word “pierced” in Psalm 22:17, this explanation is completely without merit. It is universally conceded, and beyond doubt that the rabbis who created the original Septuagint only translated the Five Books of Moses, and nothing more. This undisputed point is well attested to by the Letter of Aristeas, ((This Letter of Aristeas (2nd-3rd century B.C.E.), written by a Hellenistic Jew, describes the events leading up to and surrounding the writing of the original Septuagint. There is considerable disagreement as to the date when this was written.)) the Talmud, ((Tractate Megillah, 9a.)) Josephus, ((Josephus, preface to Antiquities of the Jews, Sec 3. For Josephus’ detailed description of events surrounding the original authorship of the Septuagint, see Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, XII, ii, 1-4.)) the Church fathers, ((For example, St. Jerome, in his preface to the Book of Hebrew Questions, addresses this issue and concedes that, “Add to this that Josephus, who gives the story of the seventy translators, reports them as translating only the Five Books of Moses; and we also acknowledge that these are more in harmony with the Hebrew than the rest.” Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Peabody: Hendrickson, Volume 6. P. 87.)) and numerous other critical sources. In other words, these ancient 72 rabbis did not translate the Book of Psalms. The Book of Psalms belongs to the third section of the Jewish scriptures called the Ketuvim, the Writings. This is an entirely different segment of Tanach from the Torah, which was the only section translated by the 72 rabbis. In essence, this missionary argument is predicated on a fabrication.

Furthermore, even the current Septuagint of the Five Books of Moses is almost entirely a complete corruption of the original Greek translation that was compiled by the 72 rabbis more than 2,200 years ago at the request of King Ptolemy II of Egypt. ((Ptolemy II, also known as “Philadelphus,” reigned from 283 to 245 B.C.E.)) This fact is well known to us because the Talmud ((Tractate Megillah, 9a-9b.)) records how these 72 translators distinctly rendered 15 phrases of the Torah in their translation. Of these 15 unique translations, only two are extant. ((Of these 15 phrases which appeared in the original Septuagint (Genesis 1:1; 1:26; 2:2; 5:2; 11:7; 18:12; 49:6; Exodus 4:20; 12:40; 24:5; 24:11; Leviticus 11:6; Numbers 16:15; Deuteronomy 4:19; 17:3), only Genesis 2:2 and Exodus 12:40 are found in the current Septuagint.)) It’s clear that the Septuagint’s version of the Torah is a corruption of the original translation made by the 72 Jewish scribes. In addition, the rest of the Septuagint is a translation by Christian scholars with a strong motive to twist the messages of the Jewish Bible.

The Septuagint that is currently in our hands—especially the sections that are of the Prophets and Writings—is a Christian work, doctored and edited exclusively by Christian hands. That said, there is little wonder why the Septuagint is so esteemed by Christendom, particularly by the Greek Orthodox Church, which regards it as Sacred Scripture. (I address the subject of the unreliability of the Septuagint more thoroughly in an article entitled, A Christian Defends Matthew by Insisting That the Author of the First Gospel Used the Septuagint in His Quote of Isaiah to Support the Virgin Birth (see page 51 and Volume 1 page 49-51).

Although Christendom is predisposed to a reverence for the Scriptures written in Greek, the children of Israel regard only the Hebrew Bible given to us by our prophets as holy and authoritative. We diligently pore over these sacred texts day and night. No translation of the Bible, no matter how widely used by churches and academicians, has any sanctity or authority among learned and pious Jews, because it is universally regarded by the Jewish people as a corrupt text.

Do not think in your heart that the Jewish people have missed the stirring messianic message contained in Tanach, or that we somehow do not understand our own Bible. It is our nation which is ordained to protect the integrity of these Holy Scriptures, our people who brought these sacred Oracles to the world’s nations, and it is our people to whom these promises were addressed.

With best wishes for a happy and healthy New Year,

I remain very sincerely yours,

Rabbi Tovia Singer